Although the practice of declaring the existence of dragons in unmapped portions of the world was not as widespread as its popular reputation would imply, the practice did happen, which is always a bit of an interesting fact for those of us who occupy the continents that were previously marked as dragons, which are mostly North and South America.

Although the practice of declaring the existence of dragons in unmapped portions of the world was not as widespread as its popular reputation would imply, the practice did happen, which is always a bit of an interesting fact for those of us who occupy the continents that were previously marked as dragons, which are mostly North and South America.Other than the Americas, however, the world has been pretty well known for a long time. Limited and indirect trade existed between the Roman Empire and the Chinese, and an entire civilization existed amounting to the collision between Hellenestic religion and Hindu religion caused by Alexander the Great. The result was that by the end of the 1st Century, a chain of parts of the world that knew about each other could readily be constructed from Britain to Japan. Thus as the Age of Exploration kicked off, the central question was not, as popular lore would have it, whether the Earth was flat (a problem that had been basically resolved some millennia prior), but how difficult a Western passage to India would be, and how big the Earth was. Pre-Columbian maps such as the Erdapfel showed Japan and Europe, and assumed a single ocean laid between them. What was assumed to be The Ocean turned out in fact to be one of two oceans with a big continent inconveniently dropped in the middle.

Thus another way to conceptualize America is as something that is defined by its interfering relationship between the extreme points of Asia and Europe. The extreme point of Europe is Britain, the endpoint of the Roman Empire, and the perennial outsider of European affairs. While, geographically speaking, Japan has fulfilled a largely similar role in Asia. The Americas, then, are the inscrutable balance point - the thing that prevents Japan and Britain from congruence. This conceptualization of America immediately makes two things clear. First, my sister is very clever for being an American in England to study Japan. Second, American Exceptionalism is a wildly boring theory compared to its alternatives.

In practical terms, British colonization of the Americas happened most successfully, and is a story we basically know. Japanese colonization, for all practical purposes, came in three waves. The first was prehistoric, as evidenced by archeological finds such as Kennewick Man, and was extremely successful right up until the first major wave of European colonization systematically exterminated them. The second came in late 1941, and was an unmitigated disaster. The third commenced with advance waves in 1978 and 1980 followed by a full-scale invasion on October 18, 1985. This third wave was both the most subtle and potentially the most successful.

Both Britain and Japan colonized me. Britain did it both genetically, as a white American dude (and 1/4 Welsh. Represent! Or is that ryypryysyynt? One never can tell with Welsh) and through Doctor Who, about which I ought talk more, but not on this blog. Japan, on the other hand, comes through Nintendo. To identify as being part of the Nintendo Generation is to admit to colonization.

Colonization is a loaded term in many ways, and I ought be careful about appropriating it. All the same, it is striking how much of my life's cultural touchstones were either created in Japan or heavily indebted to Japan. All of this is true despite the intense exoticizing of Japan within my chosen subcultures - the way in which hentai, panties in vending machines, and schoolgirls are broad-based stereotypes. In fact, it is this interplay that seems to me most puzzling about this. Japan owned the cultural apparatus when I was growing up. Japanese studios produced the cartoons I watched and the games I played. They made most of the televisions my generation played them on, and the cars we were driven in to buy them. They built the infrastructure of my childhood.

Despite this, they were made into exotic Others for my amusement. Consider martial arts like karate. Growing up, I had several friends who did karate. But what this meant in practice was that a spiritual discipline - which is basically what karate is - turned into a way of making eight year old white boys feel like badasses. Which, let's face it, is not exactly a case of addressing a genuine problem. Nobody has gone around elementary schools saying "You know what the problem here is? The boys just don't have enough opportunities to be physically aggressive."

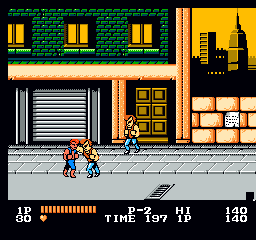

Which actually manages to bring me to Double Dragon and allows me to maintain the insane pretense that this blog is about video games in some fashion. There are three Double Dragon games. They form a classic series, but the word "classic" here needs to be taken with somewhat more salt than usual. Double Dragon 1, for instance, is not a very good game - slow, a bit awkward, and with bizarre technical limitations that culminate in the downright bizarre restriction that only two enemies can appear on screen at a time, a restriction that renders the game sort of perpetually dull. Beat-em-ups of this sort tend to depend on the problem of giving you more enemies than you can handle. Essential to the beat-em-up mechanic is that any given enemy is pretty easy, and it's when you have to deal with a horde of them that it gets tough. When you can't actually have a horde, it's not that the game becomes easy necessarily, but it does become... well... dull.

Much of this is due to the fact that the game is an arcade port - a common phenomenon on the NES. Arcade technology generally far surpassed the technology of home consoles (one of the many reasons that arcades were still powerful forces then, and are all but dead now), and so home versions were often strangely inadequate - the sprite restriction being a primary example. Though perhaps the strangest change between arcade and NES is the fact that the arcade had a two player co-operative mode in which, after beating the final boss, the two players had to fight each other to decide who won the girl, offering what is perhaps the most reductionist version of woman-as-object in video gaming to date. (Though the start of the NES version, in which a guy walks up to a woman, punches her in the face, and walks off with her is uncomfortable in its own right)

But it's never been the gameplay that made Double Dragon iconic. Rather, it was that it was among the earliest video games to have a truly ruthless sense of cool. Steeped in Japanese trappings, it is a game that channels the appeal of karate into a version that required none of the actual dedication and philosophical junk that made karate a bit of an awkward fit for the modern American prepubescent boy. In short, it is an intensely Japanese game about white boys punching things.

It is in Double Dragon II that things get somewhat weird. Part of this is due to the control scheme, which has changed to a relatively counter-intuitive one in which each button attacks in a different direction. These directions are objective - that is, one button always attacks towards the right of the screen, the other to the left. Your character, however, punches in front of him and kicks behind him, meaning that which button is which attack depends on which way the character is facing. This is, to be blunt, awkward.

It is in Double Dragon II that things get somewhat weird. Part of this is due to the control scheme, which has changed to a relatively counter-intuitive one in which each button attacks in a different direction. These directions are objective - that is, one button always attacks towards the right of the screen, the other to the left. Your character, however, punches in front of him and kicks behind him, meaning that which button is which attack depends on which way the character is facing. This is, to be blunt, awkward.But the weirder portion is the fact that the game is set in a post-apocalyptic New York that is promised to happen in 19XX, i.e. somewhere within the next 11 years given that the game was released in 1989. The depths of irony of Japan entertaining American children with a story of martial arts in a post-nuclear new York are beyond what can be conveyed by anything other than the object itself. The game is sharper, more angular and harsh. Where Double Dragon had an almost cartoonish look, Double Dragon II looks as violent as it is. This fits with its focus on the post-apocalyptic setting, but makes the game even stranger.

This game speaks volumes to the nature of our colonization. By 1989, American youth culture was so redefined by Japanese culture that it is possible for a game in which a country that we dropped nuclear bombs on fantasizes about our own nuclear annihilation to become mainstream entertainment. I am not naive enough to credit the substantial liberalization of my generation and the decline of the fear of nuclear war on a single video game. On the other hand, it is not trivial that a generation grew up actively globalized and being entertained by a post-nuclear society. These things matter.

But it is perhaps Double Dragon III that is strangest. The game plays with typical late-NES sequel sloppiness - graphics feel rushed, flat, and lifeless. But conceptually speaking, the game is completely nuts, involving running around the world collecting Rosetta Stones, of which there are apparently several now, so that they can eventually fight Cleopatra. Sadly, the plot was sanitized for NES release, not in the sense of censorship but in the sense of adding sanity. But it is here that the end result of these lines of thought converge. Double Dragon III is, at last, a game in which the US is fully subsumed into a globalized pleasure.

But it is perhaps Double Dragon III that is strangest. The game plays with typical late-NES sequel sloppiness - graphics feel rushed, flat, and lifeless. But conceptually speaking, the game is completely nuts, involving running around the world collecting Rosetta Stones, of which there are apparently several now, so that they can eventually fight Cleopatra. Sadly, the plot was sanitized for NES release, not in the sense of censorship but in the sense of adding sanity. But it is here that the end result of these lines of thought converge. Double Dragon III is, at last, a game in which the US is fully subsumed into a globalized pleasure.Where once we were the dragons on the map schisming the known world, now we are the very mouth of the Ouroboros, clamped down tight upon ourselves. If we are a global superpower and exceptional, it is because we are a cipher, the still blank part of the map that connects one end to the other. The endlessly colonized chewtoy of the antipodes. This is not to minimize the lolling dinosaur that is American power, but to contextualize it. Our power comes because when you place dragons at the fringes of a spherical map, you place them at the heart of it.

When all roads lead somewhere, that place is no longer a place. The Nintendo Generation is not some new Lost Generation of ex-pats. Rather, we are far more terrifying - the Found Generation.

Wow.

ReplyDelete...yes, I think I'll be subscribing via RSS, definitely...

Very interesting blog. I always thought that the way video games marked the culture here is quite under-recognized by much of the older generation.

I myself never owned a console, actually - only a 3/486 PC, and the staples of my childhood were games like Commander Keen, Bio Menace and Jazz Jackrabbit, none of which originated in Japan.

Much later on, I realized that the number of people who played those iconic DOS games is absolutely dwarfed by the number whose childhood staples were Sonic and Mario (which I didn't get around to playing until over a decade after they came out).

The Commander Keen community is still around making mods & fan sequels, and a few people even include Keen tributes in that modern equivalent of folk art, Flash animations (notably, TMST). But they're dwarfed by the huge number of sprite movies and "parodies" that people create featuring mostly characters from Nintendo and Sega systems:

http://www.newgrounds.com/collection/videogameparodies

But the actual foundation of both of those cultural properties is a weird syncretism that's just incredibly bizarre, at least as bizarre as the syncretism between the Hellenistic and Hindu worldview that came about in the Indo-Greek Kingdom.