So there's a woman. She wants to find Princess Gwaelin. And she spends her days standing near the fountain in the king's courtyard, pacing around. And if you talk to her, all she will do is ask where she can find Princess Gawelin. She never leaves. She never sleeps.

What can be said about this woman?

Very little. She is a phantom, in many ways. An illusion of a life. Not even a convincing illusion - no player of Dragon Warrior reasonably ponders her nature or her future. There is no way to appease her, or satisfy her - the game ends with Princess Gwaelin's location anyway. She is not even a person, but an expression of anguish, the establishment that this missing princess thing is kind of a big deal, that has been given a generic sprite and used as decoration in the same way that some people use peace lilies.

A reader wrote-in to praise the blog, but also to note that he disagreed with me about Japanese RPGs.

You were spot on when you said that live role-playing like D&D offers people a chance to share deep interactions without the emotions involved ever spilling over into real life. It sounds like as a teenager you were able to find a group of like-minded people with whom you could enjoy an activity like this. I never did. For me, human interaction was defined by keeping as low a profile as possible in order to avoid the constant threat of humiliation. Until about my senior year of high school, other people my age were pretty much the last people I ever wanted to deal with, so what attracted me to RPGs was that the characters weren’t real. Characters in video games never called me a faggot and threw pencils at me. They never stole my diary and read it aloud in class. They never told me they loved me and then sucked my best friend’s dick in the back of a Volvo.I was moved, especially because I was working on playing the games for this entry anyway, so it was of immediate relevance to my thought. I went back to Dragon Warrior III, and tried to view the characters through the light of their unreality. And the problem I had was this - the characters never told me they loved me or sucked my best friend's dick in the back of a Volvo. And really, I couldn't know that last one for certain. Because the characters in Dragon Warrior not only aren't real people, they're not even unreal people. They're not people at all.

None of which makes me sympathize less with or doubt my reader's e-mail. I take at face value that Japanese RPGs offered genuine comfort growing up. But I can't quite escape being troubled by the nature of this escape.

None of which makes me sympathize less with or doubt my reader's e-mail. I take at face value that Japanese RPGs offered genuine comfort growing up. But I can't quite escape being troubled by the nature of this escape.Dragon Warrior was in many ways the first JRPG, predating Final Fantasy by a year. In 1986, when the game was released, the NES was in its infancy - well-established by then in Japan, but still in its early days. Dragon Warrior predates Mega Man, Castlevania, Metroid, Super Mario: Lost Levels, and Adventure Island all. In the US, the system had only been widely available for three months when the game came out in Japan.

In other words, there is no genre that this game fit into. Dragon Warrior is an act of creation. The starting point of a new genre.

The thing about the Dragon Warrior games, and JRPGs in general, is that they try very actively to defy what I consider to be pretty steadfast rule about video games, and really fiction in general - there is no such thing as a fictional world.

I base this not on cynicism, or on anything less than a completely reverential respect for the transformative power of art, but on the sense that the idea of fictional worlds is a cop-out - a cheap move that devalues art. It is not that I object to the idea that art creates new things, but rather that I object to sequestering those things off behind a veil, declaring that the membrane between the world of forms and the world of representation is impermeable.

But the JRPG defies that. Not only do they set up something with a striking formal resemblance to a world - lots of video games do that - but then they try to put an elaborate plot in it with double-crossing and betrayal and rising/falling action. At their current endpoint, with things like Kingdom Hearts, Final Fantasy XIII, and other such bits of epicness, the case can almost be made that these demonstrate video games as a fully functional narrative medium with interactive virtual worlds.

Almost.

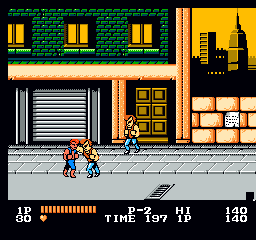

Almost.But this is not a blog about the present except inasmuch as it is held hostage by the past. And in 1986, Dragon Warrior did not have an elaborate plot. Its plot was as minimalist as Zelda, released three months earlier. And unlike Zelda, battles in Dragon Warrior were bloody tedious, with a truly epic early slog hacking apart red slimes being necessary to have a snowball's chance in hell at survival.

What distinguishes it, then, from the American style of CRPG exemplified by Ultima and Wizardry? One thing. You don't create your character. Which sounds like a negative, except for two things. First, character creation is a profoundly non-intuitive process. Optimizing character creation so that you can do well in the game requires understanding the game's systems to know, for instance, whether a boost to DEX or STR (and it's up to you to know what those abbreviations mean) are going to optimize your damage-per-round, and which one is most easily dealt with through use of magical items and leveling later. When you first boot up a game, you are unlikely to know these things, making character creation a kind of intensely futile process.

(This is why, for fans of tabletop role-playing games, there is something almost sacred about character creation. I have a friend who we joke cannot make a character unless he actually rips out a small part of his soul to imbue the character with life, so intensely dedicated is his character creation. I am less fond of the process, but strangely drawn to games like the original Traveller, where, memorably, you can die during character creation, which seems to me to be such a perfect example of the inherent madness of RPGs.)

But in Dragon Warrior, you hit start and are given a character. You can name him. That's about it. Past that, you are expected to slot into a role the game has mapped out for you. But what's interesting is that this is less of a virtual world than the American style. In those games, you can usually make a character of your choosing and expect the world to respond to you. Here, you are given the opportunity to play out the role of one character. There may be a few limited branching points, but by and large, your role is part of a larger system with all the motions pre-ordained. Your task is to live up to your role.

This is explicit in the Dragon Warrior series, where your role is defined by your being a descendent of Erdrick. This is why you have responsibilities, and why you must fight the Dragonlord. Thus instead of being put into a world and allowed to interact with it, you are given a responsibility. The video game is a duty.

This is explicit in the Dragon Warrior series, where your role is defined by your being a descendent of Erdrick. This is why you have responsibilities, and why you must fight the Dragonlord. Thus instead of being put into a world and allowed to interact with it, you are given a responsibility. The video game is a duty.(There is an interesting analysis to be made of CRPGs in general as Marxist parables - the so-called grind of leveling reduces combat to a sort of industry, with low-level monsters existing only as commodities to be tediously slaughtered by those at the low end of the corporate ladder. The adventurer is alienated from the looting of his slaughter.)

This sense of duty in video games is normal - in fact, most games do not give you much say in who the protagonist is. But it is unusual in a role-playing game that one should actually have a prescribed role. And the constraints levied by the role only increase from game to game. Dragon Warrior II has a much more involved plot that is affected in part by events of the first game, thus intensifying the sense that one's role has a pre-ordained course. In Dragon Warrior III, this heightens even more as the player is cast as Erdrick himself, and in Dragon Warrior IV, one spends the first four chapters of the game playing supporting characters trying to get to the main Hero of chapter five, meaning that by the time you get your main character he's the fulfillment of the plot as opposed to the primary instigator of it.

(Complexity of plot is actually much of what distinguishes the four games, which are otherwise pretty similar - combat against multiple opponents gets introduced in Dragon Warrior II, party management in Dragon Warrior III, and probably something in Dragon Warrior IV, but really, my eyes were kind of glazing over by then.)

It is often, and I think wrongly, said that what distinguishes JRPGs from Western RPGs is the density of plot. But off-hand, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, Mass Effect, and Planescape: Torment all have plots that are at least as complex as those of JRPGs. Rather, I think it is this sense of duty, of integrating your actions into a defined narrative, as opposed to driving the narrative, that defines the JRPG.

Which has, I think, always been what has alienated me from the genre. I do poorly with duty. Not that I am irresponsible - hell, between this and TARDIS Eruditorum I'm actually keeping a five-day-a-week blogging schedule on top of teaching. Just that I have what I think is technically known as "authority issues." I do better with games that have a sense of play in them than ones where I have duties to perform.

Which is the heart of it. My childhood, at least in the NES days, was much like what my reader described - isolating and scary. I suspect mine got better before his did, unless I was just frighteningly naive about when the dick sucking started. But in the end, I was never one to take on some other duty in some other world. It is not that I dislike the forms and systems of fiction, but rather that I have always wished to play with those systems and learn to take them apart and put them back together.

But on the other hand, thinking about the Dragon Warrior games, it occurs to me that there is another way to view it. That the Dragon Warrior games, and JRPGs in general, offer the chance not to be somebody else, but to be somebody around whom the world is designed. To have a neat, tidy, and entertaining role in the world. In the end, they are not about being whoever you want, but rather about being someone who is wanted by the entirety of a world, however threadbare that world may be.