Part 2 of an occasional series on the Disney Afternoon. Part 1 is here.

Forbidden knowledge comes in exactly one form - the knowledge of why the knowledge is forbidden. Self-referential in the extreme, it is a self-destructing idea, because once it is known it is no longer desirable. We wish to un-know the knowledge. However there is no way to un-know. Lacan suggests that there are two kinds of negation. The first, Verneinung, is the negation of "Not" and forgetting - the concept is first allowed to exist, and then marked as "not" existing. This does not obliterate it, but creates a new concept, the not-object. (Consider the double negative. "I'm not not telling the truth" is not the same as telling the truth.) The second, Verwerfung, is total erasure - the denial of the object's existence in the first place. Verwerfung, what is desired as the result of forbidden knowledge, is impossible - Lacan claims that Verwerfung is the domain of the psychotic.

When last we left this topic of the Disney Afternoon, this is the problem we ran into - forbidden knowledge creates a desire not to know. Lack of forbidden knowledge creates a desire to know. Since 1991-92, I have acquired forbidden knowledge, rendering the desire to recreate 1991-92 impossible without psychosis.

New path. This one is based on a comparable process, in the hopes that by understanding that process we'll be able to transplant the knowledge to another sphere. First, Darkwing Duck. The most recent addition to the Disney Afternoon in the year in question, it is a superhero pastiche. I remember with some vividness the debut of it. Previewed and hyped for some months prior, the show was touted as the sort of cultural event I've discussed previously.

For my part, I bought into the hype. I wanted to see it. I waited for September 8, 1991 with active excitement - an excitement that rivaled my excitement for my 9th birthday the next day. This is not an uncommon occurrence, both in my life and in the broader culture. Movie releases, TV season finales, video game launches, all of these are moments that we look forward to with almost ritualized eagerness.

I did not grow up with a particularly large capacity for religiousness, nor even spirituality. I will not speculate on why. Suffice it to say that there were not, in my childhood, a wealth of spiritual moments. Moments like the anticipation of Darkwing Duck were the rare exception.

This remains the case to this day. Four times in the last decade, I made scheduled pilgrimages to midnight launches of Harry Potter books. I would take them home, and read them for as long as I could stay up for, then would fall asleep, wake up, and read them with equal zeal until they were done, finishing off the event in mere hours.

This ritual is a fundamental part of my life. I engage in it every Wednesday, going to the comic shop to discover the newest developments in my favorite serials. More significant milestones come in the release of works by favorite authors - of late a new Alan Moore, although new works by Grant Morrison, Neil Gaiman, or Greg Rucka are afforded similar stature.

It is not that the anticipation of these events exceeds the event, although, to be fair, in many cases the end result is more fizzle than mystical transcendence. Still, at times the event lives up quite nicely. The Battlestar Galactica series finale, Serenity, and The Brothers Bloom - three of my favorite artistic experiences in recent memory, were all eagerly anticipated and rushed off to see at the earliest opportunity. On the other hand, The Fountain, although I was aware of it and thought it looked really cool, was not an "actively keep track of it to grab at the first opportunity" kind of movie. It was also the best movie I've ever seen.

And plenty of art that just completely blew me away crept up on me. I bought Promethea on a lark. I had no idea Copenhagen was going to be such a great play - I took my dad to it because I figured he'd enjoy it. And there's plenty of art I noticed long after the fact - Watchmen, Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Sandman - these were all well and done when I first discovered them, and grabbed me with no anticipation.

Stil, the anticipation of art is a fundamental pleasure of life that I would not for a moment trade away. Why? The cynical answer would include some reference to "finding out what happens," but this misstates why I drove 45 minutes each way to get to a bookstore that had Neil Gaiman's American Gods the day of release. It did not feature any recurring characters, or advance a story I was already invested in.

And at the best of times, my views on investment in stories are esoteric. I routinely berate my students for intellectual sloppiness on this point. I am hesitant to treat fictional works as taking place in worlds that just happen not to be real. I believe firmly in a narrative logic that is distinct from actual human psychology. A classic example is cartoon physics. It is not merely that physics work differently in a Road Runner cartoon. It is that they are not actually physics in any sense that we understand them. It is not as though instead of F=MA F=2MA. Rather, F=whatever is funniest. Or, more specifically, F=whatever is funniest within the domain of discourse of a Road Runner cartoon and the available jokes within that framework. F does not equal, for instance, political satire. But F is far more defined by narrative and aesthetic concerns than it is by any sort of mathematical model.

Given this, it is not as though I care about the fates of fictional characters as such. Even in the case of an enormously poignant fictional death, I do not mourn as though a real person has died. My emotional investment is far weirder and more complex than that.

I say all of this to stress why I await art with a sort of spiritual reverence that I do not proffer to such delights as, say, dinner. Because work of art provide a unique sort of knowledge - one that is, as the cliche goes, more true than truth. Consider - everything we know about the history of science suggests strongly that eventually something will happen that will completely unsettle and overturn our understandings of physics. The entire model of physics we have right now very probably needs a fundamental adjustment. Why do I say this? Because every previous model has.

So when we say something like "the strong nuclear force binds neutrons and protons together," we may well be wrong, despite the fact that this is a true statement about objective reality. On the other hand, when we say that "Hamlet's father was murdered by his uncle," we are making a statement of absolute, unequivocal truth - one that it would be very difficult to alter the truth of. Artistic truth is unique because it has a real shot at universality, and even that most elusive of qualities, ontology.

I await art with reverence because it is a revelation of truth - because once art exists, and I am interested in it, the knowledge it contains is too precious and too alluring to resist.

Art is just as transformative as forbidden knowledge, demarcating a clear before and after that can only be traversed in one direction. Unlike forbidden knowledge, artistic knowledge is edifying in hindsight. We look back on art not as a moment of "loss of innocence" or somesuch, but rather as a moment of enlightenment.

The thing is, because art produces a desirable result, we wish to recapture it. Here is where it differs most fundamentally from forbidden knowledge. Forbidden knowledge is that which, once we know, we wish to unknow. Artistic knowledge is that which, once we know, we wish to reknow. But unknowledge requires awareness of that which is unknown. It is not sufficient for me to not know the forbidden knowledge - this does not fulfill my desire to unknow it. I want to know that I do not know it. Similarly, I cannot simply reread a favorite book to recapture the artistic knowledge. I must somehow forget the book sufficiently to revisit it.

Unknowledge and reknowledge are thus recognizable as the same thing. Art and forbidden knowledge are opposite poles on a cycle of experience. They are not interchangable - rather, they are two parts of a larger object that we may call thought.

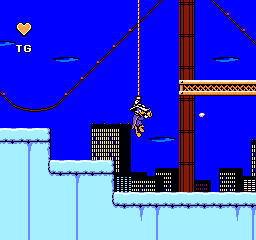

As a game, Darkwing Duck feels ahead of its time, although this knowledge is more hindsight-ridden than usual. Darkwing Duck, in the game, is capable of grabbing and holding onto most of the surfaces in the game. This gives it a feel somewhat like Bionic Commando. Most of the ledges exist for the purpose of enabling you to get an item or shoot an enemy. Thus Darkwing Duck's range of motion becomes an illusion of freedom. You can go anywhere you want, but anywhere you can go is probably just somewhere to shoot someone.

In the contemporary world of video games, this structure is common - I just finished Batman: Arkham Asylum, and the similarities were striking. Ostensibly a game in which Batman can freely explore the asylum instead of sticking to the pre-ordained path, almost anywhere Batman can wander has a reward or a challenge to complete. It suffers from most of the weaknesses I identified in previous Batman games, but looking at it, one aspect in which it captures accurately "what it is like to be Batman" is this - Batman is, in the game, ontologically defined as "that which has to go around and fight things." There is no rejection of the basic premise of the game. Batman can do anything he wants as long as it's solve all the challenges in Arkham. Even more perversely, the game's reward structure is challenges. That is, when you accomplish something, the result is generally to cause you a new problem to overcome. Your reward for success is being bothered with more shit to do, thus keeping you on task by multiplying the number of things you are asked to do such that any action advances your tasks.

But in 1992, when Darkwing Duck came out, this structure was not how video games worked. Thus grafting it onto a side-scroller was creative and original. Played in hindsight, it's a prototype - a piece of nostalgia and history. This is true even though I never played the game.

Ironically, my reverence for impending art applied to this post - I've been looking forward to it since Chip 'n Dale, and known that it would be my post about waiting for art. Now that I've mostly written it, I'm irritated - I can see all the spots where the argument didn't quite hold, where what I wanted to say didn't come through and I had to settle for ambiguities in place of certainties, or certainties in place of ambiguities. I expected it to be great - a good topic, what was probably going to be a good game, given that Capcom's Disney games are mostly pretty good, an ideal candidate for an archetypal Nintendo Project entry, and one I could probably make more accessible than the relative weirdness of the last few.

Now I've written it, and all that is left is a dead game, understood as all too bound up in time and history. Something that points to part of a larger narrative about video games that is endlessly glimpsed but never seen. Through my cycle of unknowing and reknowing, I seem to have broken the object itself.

This is the danger in mythologizing. One does not always like what one creates. I am not even talking about dark and terrible things - myths that scare and alarm, terrors that flap in the night. I am talking about a worse fate - mundane, banal, pointless myths, lovely quicksands that intrigue, suck up time, and offer no sustenance, no enduring results.

We are going to need something more enduring. A firmer foundation upon which to build our mythos.

regarding your reverence for artistic truth...how do you feel about retcons?

ReplyDeleteI bet duck tales will make up for your irritation! and did you leave out adventure island (or are you waitin for H, hudson's)?

Hello, oh fellow Connecticutian.

ReplyDeleteRetcons are fascinating to me. I tend to think it's impossible to alter the existing text - my standard example is that the escape Sherlock Holmes describes in the story he makes his return from the dead in is completely implausible in the context of the story he dies in - there's no way any sane reader would think Holmes might have escaped that way. Mostly, retcons seem to me to be a strange quirk of the fact of serial narrative, and to suggest that it is not quite accurate to treat a long serialized narrative as a single narrative.

DuckTales is a great game, and I am looking forward to it. And yes, Adventure Island is under H.

this state just churns out awesome people! how about that governor's race?

ReplyDeleteI like that you have a standard retcon example, though s.h.'s comeback epitomizes the worst kind, don't you think--forced by public clamoring against the will of the artist. not sure if you're into batman but the return of badass jason todd has been really enjoyable!

Heh. Where in the state are you? I have not found awesome people. It is getting depressing.

ReplyDeleteI'm very much into Batman, though mostly focusing on Grant Morrison's stuff. But I think Jason Todd has been a textbook example of public clamoring, albeit in a weird way. Once his death became an object of nostalgia, and he got defined as "the character so annoying fans voted to kill him," bringing him back became a matter of giving the fans the exact character they remembered. The actual Jason Todd as Robin era is relatively calm, business-as-usual Batman. Because up until the issue where he died, nobody was planning on defining the character by his death. But the utter weirdness of his death changed the perspective of the character. All the same, I don't think you can pick up a mid-80s Batman story and argue convincingly that the Jason Todd there is in any way a meaningful setup for the Red Hood Jason Todd. They're essentially different characters, with the latter being the revival of the character that fans, in nostalgia and memory, mistook the former for being. But the stories don't follow from past events at all - they're straight-up responses to comics fandom and its internal mythology.

cheer up! you haven't met me yet! I'm in danbury.

ReplyDeleteyeah, you're right about jason todd...my parents cut me off comics after only a couple years, and I never knew (the first) jason. I guess rage and rebelliousness are hardly character attributes, and his 5 year existence was a blink in comic-time anyway. does any retcon in particular appeal to you?

Oh, Danbury? Seriously? You're right down the road then. (I'm exits 9-11 of I-84)

ReplyDeleteI actually, for all that it is, quite like the Sherlock Holmes retcon, which lets Holmes have a big, epic, apocalyptic story that would normally be impossible for him, then lets him keep going on telling stories. I also generally really like the Grant Morrison Batman stuff, which has heavily retconned the Silver Age, but done so in a way that seems to me to let his stories and the old stories stand side by side instead of in conflict. His revamp of the New Gods in Final Crisis was also pretty sexy.

And Doctor Who, of course - the series that retcons itself damn near every episode, given that it has zero sense of continuity at all. And is my absolute favorite TV series.