I have commented in the past that video games are a poor medium for narrative because, truth be told, most narrative is not based on taking breaks for fight scenes with obsessional frequency. In truth, this is ever so slightly a misrepresentation - a fight, after all, is defined primarily by struggle and tension. This is what we all learned watching Fight Club - after we learned not to talk, I mean. Fights are long, brutal occasions. "A fight will go on as long as it has to."

I have commented in the past that video games are a poor medium for narrative because, truth be told, most narrative is not based on taking breaks for fight scenes with obsessional frequency. In truth, this is ever so slightly a misrepresentation - a fight, after all, is defined primarily by struggle and tension. This is what we all learned watching Fight Club - after we learned not to talk, I mean. Fights are long, brutal occasions. "A fight will go on as long as it has to." I got into two fights in school. One was after school, at some event or another. Several kids were playing on top of a cement structure of some sort. One, named Greg, pushed me off. I fell on a rock, picked the rock up, and threw it at him. What followed can best be described as "me running like hell as he chased me down, and when that failed to keep working for me kicking hard towards his groin." The official score as recorded by people more popular than I was "Greg kicked the shit out of me." In my view, it was a draw.

Video games are rarely about an extended struggle. Rather, they are about a vast sequence of enemies that are taken out quickly and in rapid succession. The video game is either about a death by a thousand paper cuts, or about simply fighting perfectly for a reasonably long stretch because one hit will kill you. With Greg, on the other hand, it was a far more extended affair - fast moving, but defined by minute attempts to gain physical dominion over the other.

Bad Street Brawler belongs to a more or less abandoned video game genre called the Beat-em-Up. This genre is one of those wonderful things that does exactly what it says on the tin. You walk in a more or less straight line. Hordes of enemies mob you, often from both sides. And then... you beat them up.

I had exactly one fight like this, and I forget who it was with. It was in gym class. Someone provoked me somehow, and I charged them. They landed a single sucker punch right in my unguarded face, and that was the end of that.

To call that fight unsatisfying is an understatement. Perhaps whoever the jerk was enjoyed it more than I did, but honestly, I suspect it was kind of pathetic all around. This is perhaps why the beat-em-up is a basically dead genre. Nevertheless, there exist some things that Bad Street Brawler does that are unusual.

- Bad Street Brawler was one of two games to be designed for use with the Power Glove. In a neat bit of symmetry, in the classic film The Wizard, Jackey Vinson's character proclaims his love for the Power Glove on the grounds that it makes him feel so bad. (Fun fact - the love interest in The Wizard went on to be the lead singer of Rilo Kiley)

- Bad Street Brawler restricts you to a different set of two moves in each level. This has the practical effect of altering the difficulty of the game not by adding new enemies but by removing your ability to hurt them and replacing it with the ability to, for instance, spend an inordinate amount of time winding up a punch while they walk up and murder you.

- At the end of each level of Bad Street Brawler, you throw all the weapons you collected from your enemies in a dumpster. You can see in the screenshot above how you are throwing a very nasty looking ball and chain away in the dumpster. This is so next level you can trip people instead of hitting them with a giant steel ball.

Where fighting is defined by a sort of intensely combative intimacy (there's a word we should set aside and pull out later) of physical tactics and punishing brutality (the best fight scene ever is in season 3 of Deadwood, and if you go and watch the show you will know exactly which one I mean), Bad Street Brawler is defined instead by a sort of lengthy tedium - each individual brawl a mere distraction punctuating the long walk from Point A to Point B. It is not so much fighting as counting pavement stones with your fists.

My father, in his time, got in only one fight. In it, he simply continually blocked his assailant's punches with his heavy bag of books until his opponent had sufficiently pulverized his hand that he called it a day. This is perhaps the most authentic fight described here.

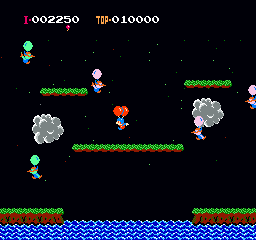

Balloon Fight is, despite its lack of actual, you know, fighting, is considerably more accurate in its depiction of a fight. There are essentially two games in Balloon Fight. In one, you attempt to take down enemy balloonists by popping their balloons without allowing them to do the same to you. In the other, called Balloon Trip, you try and fail to successfully navigate an ocean above which flies huge patterns of deadly ball lightning. There is not what you would call a "reason" why you would want to fly over this ocean. It's there, you have two red balloons, so why wouldn't you. Besides the IMMINENT DEATH, obviously.

I have thought about the ethics of the playground fight as a parent. I am not one yet, but I will be someday. And I will raise a geek. And like all geeks, shit will be bad at times, and there will come a point where my kid has to decide whether a fight is in order. What fights are worth having? Neither of mine were - both were stupid situations I instigated through a short temper and a lack of ability to deal with the consequences thereof. My father's might have been. J. Michael Straczynski likes to put the line "Never start a fight, but always finish one" in just about everything he writes. (Or at least in both Babylon 5 and Changeling, which are otherwise quite different) This is perhaps good advice, but on the other hand, what do you do with a fight you're not sure you can finish. Does it behoove me to teach a kid how to survive a fight in the event that one is forced upon them? Or should I let them get beat up in the hopes that the moral upper hand will be of some value to them later?

Balloon Trip is serviceable if silly. The actual Balloon Fight, though, has in it a certain ghost of combat, if you will - an extended set of tight, tactical maneuvers in which you try to find and

exploit the upper hand. It is not quite a good game - its classic status stems entirely from Nintendo's strange obsession with releasing it over and over again. In practice, the controls are

awkward, the obstacles cruelly arbitrary, and the value of high ground too overstated. But it has somewhere underneath it the satisfying form of a good fight - a struggle worth having.

I still don't know, however, what that means.

No comments:

Post a Comment